Upon accepting Islam, the new Muslim finds him or herself in a situation most of us are unfamiliar with and unprepared to deal with. A new Muslim is a social infant. Through the grace and mercy of Allah, I became an infant myself a few years ago when I rediscovered my fitrah (my inherent knowledge of Allah that all people are born with).

In addition to finding my fitrah, I also found that I was unable to properly perform such elementary life skills as going to the bathroom. I found myself in my own hometown struggling with basic issues of language, social norms, personal cleanliness and basic interpersonal etiquette. Navigating these hurdles and learning Islamic adab, or proper Muslim conduct, was to prove an enduring challenge.

The advantage I had over a literal infant was that I was able to read and ask questions in order to attempt to learn as quickly as possible how to be a Muslim man. Hand in hand with this adult capability was the adult knowledge of how much I did not know and understand, and how many mistakes I was making. Like many converts and ethnic Muslims alike, I strove to rectify my blatantly inadequate knowledge both by watching the Muslims around me, as well as by reading books of law.

Both routes proved to be difficult paths to tread. Except for qualified scholars, the average Muslim is wholly incapable of wading through texts of jurisprudence on his own and deriving how to live a proper Islamic life from law alone. A fatwa will definitely answer a specific question and provides an invaluable part of any conscientious Muslim’s life. A fatwa however, or a large collection of fatwas, cannot tell a preverbal infant how to behave.

When I moved from America to Egypt, it never occurred to me to pick up a copy of an Egyptian law book and peruse it on the plane ride over in preparation for my living in Egyptian society. Familiarity with Egyptian law would certainly provide much valuable knowledge to help me live in Cairo. Yet knowledge of law would not provide me with knowledge of basic life necessities, like how to catch and pay for a cab, how to be a good guest in someone’s home, or how to conduct myself in the mosque. The tools I need to cope with these situations and others are encompassed within the concept of adab.

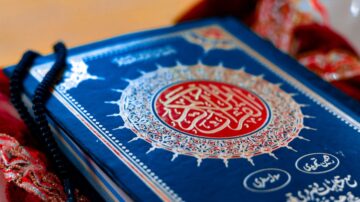

Just as Egyptians have certain manners, so too do Muslims. How does a Muslim treat his friends, his possessions, his food, or his copy of the Qur’an? How does a Muslim dress and carry himself in public and in private? The answers to these questions must first be directed from the standpoint of halal and haram (lawful and prohibited), and then go beyond whether something is merely permissible or not, and address whether it is proper Islamic adab or not. It has not been so long since I became a Muslim, but my struggle to behave like a Muslim is still in its infantile stages.

By Sam Abdul Wadoud Highsmith