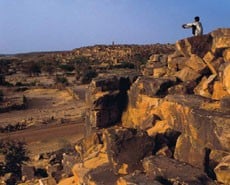

One could easily lose something precious in Mauritania’s million square kilometers of dune fields and rocky steppes, stretching north from the Senegal River and east from the Atlantic into the Sahara’s most desolate corners. Nomadic encampments are few, villages are far between, and the wind blows inexorably from the west, scattering all that comes before it.

But Ahmad Ould Mohamed Yahya, director of manuscripts at the Institut Mauritanien de Recherche Scientifique (IMRS) in Nouakchott, believes it is not a fluke that something precious should recently have been found in the small town of Boutilimit, some 150 kilometers (95 mi.) east of the capital city of Nouakchott: the world’s only known complete manuscript of a work on grammar by the great Spanish-Arab physician and philosopher Ibn Rushd, known in the West as Averroës. This find, so far from the Mediterranean basin, means that historians must rethink just how far Ibn Rushd’s writings and influence extended into the Arab hinterland.

The Fame of Mauritanian Manuscripts

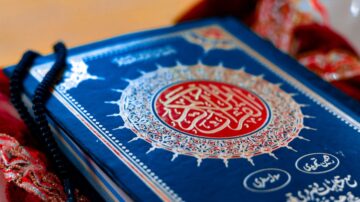

Mauritania is known throughout the Arab world—but hardly at all in the West—for its enormously rich heritage of Arabic manuscripts, many brought from the Arab East by pilgrims returning from Makkah, some recopied from those imported sources by students in the Qur’an schools that once flourished throughout the country, and others composed by Mauritania’s own jurists, poets, and historians.

“The traditions of scholarship in Mauritania during the past three centuries, albeit profoundly linked to the medieval epoch, are probably the richest in West Africa,” says Charles Stewart of the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, an expert on the country’s early modern history. “They compare favorably with [those of] Maghribi societies of an earlier date,” adds Muhammad Shahab Ahmed, a historian of Arab philosophy. “Whenever I travel in other Arab countries,” he says, “I just have to say one word—Mauritania—and everyone wants to talk to me about our manuscripts. The mere subject opens up for me so many intellectual doors in foreign capitals. The manuscripts are truly our country’s calling cards.”

The Treasurers

The great Egyptian man of letters Taha Hussein was not the only Arab from the East to recognize Mauritanians’ special affinity for collecting manuscripts. In his autobiography Al-Ayyam, translated as Stream of Days, he remembers a well-known Mauritanian scholar at Al-Azhar, the great Cairo university, Muhammad Mahmoud Ould T’lamid, a fellow at Harvard University: “The fact that the only existing copy of a work by Averroës has been preserved in Mauritania is a remarkable illustration of the southern migration of the scholarly corpus of Al-Andalus and the Maghrib”—Muslim Spain and North Africa.

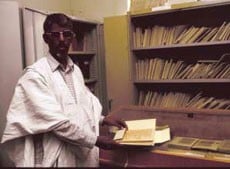

Ahmad Ould Mohamed has been traveling throughout Mauritania for more than 20 years, visiting private libraries, cataloguing their contents, and exhorting their keepers to safeguard their written treasures. “I have already seen almost 200 private libraries, some just a humble stack of pages, others quite fantastic assemblies of learning. I think I have about 100 more to go before I have seen them all. And before then, I would not be surprised to find another rare manuscript comparable with that of Ibn Rushd.”

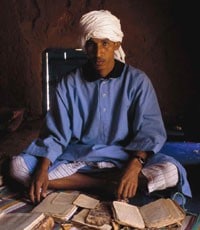

The Averroës work is called Al-Daruri fi Sina’at Al-Nahw, or What Is Necessary in the Making of Grammar, and was part of the family library of the young businessman Baba Ould Haroune Cheikh Sidiyya. “I am a librarian by accident,” he says modestly, but he is certainly more than that. The library was established by his ancestor Cheikh Sidiyya Al-Kabir (1774–1868) and added to by subsequent family savants, book collectors, and writers. Stewart has called this library “a culmination of the known and studied Islamic sciences in West Africa on the eve of European penetration.”

After the death of his father, Haroune, in 1978, Ould Haroune immersed himself in manuscript conservation work, assisting in Stewart’s cataloging of the library, helping the government establish a policy on the protection of the nation’s cultural heritage, editing and publishing the critical edition of the Averroës manuscript, and now editing his father’s own work, a multivolume historical encyclopedia of Mauritania.

“The older students mentioned a certain Sheikh Al-Shinquity,” he wrote, “as a friend and protégé of the imam. This outlandish name made an odd impression on the boy, and odder still were the eccentric ways and unconventional ideas which made this sheikh a laughingstock to some and a bugbear to others. … They nicknamed him “the passionate Moroccan” and told of the wealth of manuscripts he possessed, together with printed books not only from Egypt but from Europe, despite which he spent most of his time reading or copying in the national library.”

Ould T’lamid was also a friend of Ould Haroune’s grandfather, Cheikh Sidiyya Baba, and the Boutilimit library contains correspondence between the two, including requests to write commentaries on each other’s books. It is still a sore point for many Mauritanians that after Ould T’lamid’s death, his personal library was absorbed into Egypt’s national library rather than returned to his homeland.

To browse through the 7000-item IMRS collection is to catch but a glimpse of the country’s entire archive, thought to number nearly 40,000 manuscripts, about three quarters of them written or recopied locally and the remainder brought from Fez, Tunis, Cairo, and beyond.

The oldest work is a 10th-century copy of Al-Mas`udi’s world history Muruj Al-Dahab wa Ma`adin Al-Jawhar (Meadows of Gold and Treasures of Jewels), written on gazelle skin. There are such basic texts as the Sahih Al-Bukhari, a standard collection of Hadith (the authenticated practices and statements of the Prophet), copied and dated in the year 1872 by Hassan ibn Muhammad Al-Sirfin, and a copy of the great pre-Islamic poets’ works produced in the 18th century by Asnid Ould Muhammad Najim in a fine Mauritanian script.

A Modest Land With a Great Heritage

Unlike North and West Africa, home of such great “library cities” as Tunis, Fez, and Timbuktu, Mauritania never had large sedentary population centers. Its four historical caravan towns, Chinguetti, Wadan, Walata, and Tichitt—all now UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites—are, and probably always were, somewhat removed from the hustle and bustle of great urban intellectual enterprise. Nonetheless, they are all old towns, and their people are proud of their libraries. Wadan even claims that its name comes from the dual form of the word wadi, meaning that it was a town of two valleys—a literal valley of palm trees and a figurative valley of scholars.

Tichitt has a new manuscript conservation center which, when its staff is fully trained, will work with an 18-person association of private library keepers in nearby Tidjikja. In Walata, a team of Spanish urban preservationists has just completed a UNESCO assignment to repair the town and stabilize its economic base.

Chinguetti

Chinguetti holds the country’s greatest claim to fame. In fact, for many centuries, all of Mauritania was known in the Arab East as bilad shinqit, “the land of Chinguetti,” although the term did not appear in any of the great medieval Arab geographies. Mauritania’s most famous modern writer, Ahmad ibn Al-Amin Al-Shinqiti (1863–1913), in his geographical and literary compendium Al-Wasit, wrote lovingly of his hometown’s special charm. Today, the town is something of a showcase for private library conservation, and the French especially have lavished much attention on its first steps forward in this regard.

Four family libraries there—the Al-Habot, the Al-Ahmad Mahmoud, the Al-Hamoni, and the Ould Ahmad Sherif—are all quite well organized, catalogued, and open for both scholarly and tourist visits. In fact, much of the town’s income today comes from such visits.

The Al-Habot library is the best known and most thoroughly catalogued. Established in the 18th century by Sidi Muhammad Ould Habot (1784–1869), a descendant of Islam’s first caliph Abu Bakr, it grew through wholesale acquisitions of libraries elsewhere in North Africa as well as by copying locally available books. Now holding some 2,000 manuscripts, the collection spans the period from the year 1088, with the only known complete copy of Granadan author Abu Hilal Al-Askari’s Tashih Al-Wujuh wa Al-Naza’ir (The Correction of Appearances and Views), to the year 1980, with a more humble manuscript written in ballpoint pen on lined paper: Taqrir Hawla Al-Maktaba Al-Habot, a history of the library by the current keeper’s great-uncle.

The library of Ould Ahmad Sherif is a more humble affair, guarded by the aged notary public Muhammad Judu’, who unlocks its creaky door in a mud-plastered back-alley courtyard with a toothbrush-shaped wooden key. Ceiling panels of plaited palm fronds permit only a shadowy half light to enter the room, whose shelves contain cardboard conservation boxes, numbered into the 600s, in which the manuscripts are held. The library’s core holdings were acquired in the 14th century in Tunis during a buying trip by the library’s founder, Ahmad Sherif. One work on gazelle skin, the Sharh Mouta’ Malik (Explanation of a Royal Footstep) by Abd Al-Baqi Al-Zirqani, is thought to be in the author’s own hand, making it a particular rarity.

The Al-Ahmad Mahmoud library is kept by an energetic teacher named Saif Al-Islam, who maintains a public reading room of modern books and magazines (including a few back issues of Saudi Aramco World) for Chinguetti’s youngsters, next to the historical collection, which contains some 400 manuscripts and 1,400 documents related to local family history. Saif Al-Islam has a keen curiosity about how and why the written word travels so easily. “Our library has a Hebrew prayer book, and I was told that the Kremlin’s library has a manuscript from here,” he says. “How both got to their respective shelves I can only wonder.”

Traditional Education

Despite the intellectual capital of these town libraries, Mauritania’s scholarly strength has always been at the grassroots—en brousse, as they say in French—in the itinerant schools and rural lectures known as mahadhras, organized by charismatic teachers and scholars always on the move. Ahmad Ould Mohamed of the IMRS received his baccalaureate degree on the strength of a mahadhra-based education alone, and with it, he entered directly into law school. “I was the best prepared in my class,” he says.

One cannot overemphasize how important mahadhras once were to the education of Mauritania’s scholarly elite—and to the dissemination of books. “Mahadhra professors were both printing presses and teachers,” says Ould Mohamed. “They had their students recopy manuscripts as assignments, and since their students were not just the young, but sometimes already well-educated adults who thirsted for higher learning, these copies contained marginal notes and commentaries of importance to our local intellectual history.”

The future of mahadhras is very much uncertain, however. A national conference was recently held that extolled their legacy but worried about their long-term survival. Pessimists note how many have closed in recent years, but others believe that mahadhras can “reclaim” frustrated dropouts from standard primary schooling precisely because they provide one-to-one teaching of customized curricula, with students grouped together by interest and aptitude, not by age.

The example of former minister of justice Muhammad Salem Ould Abd Al-Wedoud is frequently cited to show how the mahadhra system might be successfully modernized by providing esteemed professors and a reliable schedule. Ould Abd Al-Wedoud teaches in several locations in the countryside and in Nouakchott, and his classes attract top Mauritanian candidates, as well as students from elsewhere in North Africa, Pakistan, and beyond.

The American teacher Hamza Yusef, who recently advised the White House on American Muslim affairs, studied at a mahadhra such as this. His Zaytuna Institute of Islamic Studies in California is modeled at least partly on his experience in Mauritania.

Indigenous Literary Genre: Nawazil

Closely tied to mahadhra education is a literary genre that has thrived in Mauritania over the last three centuries: the nawazil, or collection of legal cases presented in question-and-answer format, usually pertaining to the country’s predominant Maliki school of law.

Dedoud Ould Abdallah, a professor in the Faculté des Lettres at the University of Nouakchott, was recently in the IMRS library examining a rare copy of the nawazil of the 19th-century Mauritanian jurist Abdurrahman ibn Muhammad ibn Talb N’buya Al-Walati, a native of Walata. “I am looking for variations between this copy and another I have previously consulted,” he said, “to help clear up a historical discrepancy. Copyists frequently made mistakes in the main text, but it is very instructive to have their own marginal notes as a guide.”

Ould Abdallah notes that the poor physical condition of many manuscripts does not always reflect poor storage practices. “These manuscripts were read, handled, and transported over the years by many students in the bush,” he says. “That some were used to the point of near destruction is only natural, just as it is natural that the same students who read them should have recopied them time and time again.”

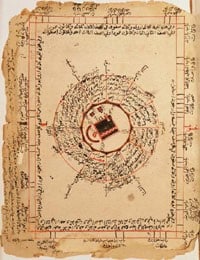

Calligraphy

Mohameden Ould Ahmad Salem is a young self-taught calligrapher who recently published his university thesis on the history and development of Mauritanian scripts. “Many people think Mauritanian scripts are purely derivative of Maghribi styles,” he says, “but this is not so. At a very early period, we adopted Andalusi calligraphy, which in Morocco developed into Maghribi, but we went our own way with it.

“Historians said that Andalusi script had long ago disappeared, but the more I looked at Mauritanian scripts, the more they looked like Andalusi. If you compare an Andalusi manuscript from the 12th century and a Mauritanian manuscript from the 19th century, they are so close in style that they could be by the same calligrapher.”

The first manuscript known to have been written in Mauritania, according to Salem, is a collection of advice on how to apply the Almoravid law code, titled Al-Ishara fi Tadbir Al-Imara, by Imam Al-Hadrami, who died in 1097. It is now in the Abd Al-Mu’min library in Tichitt, copied in fine Andalusi calligraphy. By comparison, he continues, the second-oldest local work is a book on jurisprudence by Sidi Muhammad ibn Ahmad Abu Bakr Al-Wadani, who died in 1527. It is written in a uniquely Mauritanian style called Legrayda, meaning “lobed,” because of its rounded edges. Of the four main scripts used in Mauritania, Legrayda is closest to Andalusi and the most common, as it was suited to fast, small, and compact copying. “Paper was a rarity back then,” Salem explains. “In the national museum, you can see the cannon recovered from a 16th-century Portuguese ship that went aground on our northern coast. We know that same ship also carried a supply of writing paper from Ceuta [on Morocco’s Mediterranean coast] that was salvaged by local scribes. The Mauritanian jurist Muhammad Al-Yadali mentions it in one of his works.”

The other Mauritanian scripts are Mushafi, an ornamental style for title pages, poetry, and the Qur’an; Mashriqi, similar to the Thuluth style of the Arab East, with floating adornments and sometimes outlined letters filled in with gold; and Sudani, a simple, bold student style, similar to Kufi with its angular lines and wide-nibbed pen strokes.

The Future of the Manuscripts

Salem recently addressed the First International Conference on Mauritanian Manuscripts convened by the Project for the Protection and Development of Mauritanian Cultural Heritage, an undertaking financed by the World Bank and headed by Mohamed Haibetna Ould Sidi Haiba. The project aims to coordinate the efforts of international conservation agencies—including UNESCO, the Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation established by Ahmad Zaki Yamani of Saudi Arabia, and the Bibliothèque Nationale of France—with the work that is spearheaded locally by IMRS, the University of Nouakchott, and others.

Ould Sidi Haiba sets forth an ambitious plan to build manuscript conservation labs throughout the country. One major hurdle to clear remains the unwillingness of many keepers of family libraries to part with their manuscripts, even for the short time it would take to fumigate them against termites and stabilize their damaged paper. Many individuals see their manuscripts as a multigenerational trust, which should never leave the family’s hands.

To illustrate this feeling, he tells the folktale of Sidi Abdullah Ould Al-Haj Ibrahim, a pilgrim from Tidjikja who went to Makkah riding a full-blooded Arabian stallion that he had sworn he would never sell. In Cairo, however, he came upon a unique manuscript he could only obtain by trading his precious mount for it. When he returned home, his friends were amazed that he no longer had his horse. “Where is it?” they asked. “My stallion has been turned into a book,” he answered—and that was explanation enough in Tidjikja.

Even though controlled central storage may be essential when the holding conditions in home libraries are inadequate, many individual owners prefer to risk their manuscripts’ continued deterioration rather than hand them over to others. Forming local associations of private library keepers who agree to pool their collections, and thus create a critical mass of historical value, is another aim of the project. With reason, Ould Sidi Haiba fears that when the day comes that Mauritania’s manuscripts have deteriorated so far that they can no longer be read, recopied, or even catalogued, they will become the latest addition to his country’s “literature of memory”—folktales, tribal poetry, and genealogies—as examples of what his project calls “intangible” cultural heritage.

Treasuring the Written Word

One of the country’s most famous literary works is the Rihla, or Travels, of the marvelously named Ahmad Ould T’wayr Al-Janna, “Son of the Little Bird of Paradise.” Between 1829 and 1834, he traveled from his hometown of Wadan to Makkah and back. With most of his adventures behind him, and after having been comically mistaken for the king of Mauritania by the British governor-general of Gibraltar, Ould T’wayr Al-Janna arrived in Marrakech as the guest of the sultan. His experience there underscores just how deeply all Mauritanians treasure the written word.

“He gave much money so that I could buy books in Fez,” wrote Ould T’wayr Al-Janna. “We returned to Fez and there, God be praised, we bought with that money all the heart could desire. My son told Sultan Moulay Abd Al-Rahman of the quantity of books I had bought. He was amazed at that, and he said to him, ‘God has granted you a miracle, something quite out of the ordinary.’” But when the report came back that some scholars of Fez, grumbling that a Mauritanian was buying the best on the market, refused to sell Ould T’wayr Al-Janna more manuscripts, the sultan himself intervened, making sure “we could buy what our hearts desired.” A caravan of 30 camels was hired to take his acquisitions back to Wadan. “By God,” he concluded, “there have been seen on the trip many kinds of hopes and goals wished for and sought after, and many boons and favors granted.”

Mauritania’s Arabic manuscripts are the legacy of such visionary collectors as Ahmad, Son of the Little Bird of Paradise, and Taha Hussein’s Shaykh Al-Shinquity. It is not easy to fill their shoes, but their countrymen today—men like Baba Ould Haroune from Boutilimit, and Ahmad Ould Mohamed of the IMRS—are doing what they can to ensure that Mauritanian readers of tomorrow will always have original sources to consult and original works from which to learn their national history.

By Louis Werner**

Photographed by Lorraine Chittock***